The Brimley Line, and the work I was born for

I crossed the Brimley Line the other day.

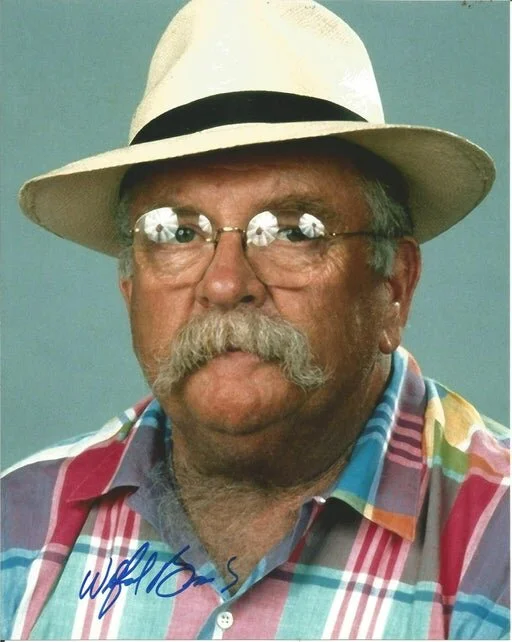

December 8, 2019, to be precise. That’s the day I turned 18,530 days old, the same age as Wilford Brimley the day the movie Cocoon hit theaters. Cocoon is about very senior citizens who… well, it doesn’t matter. There are aliens, and Wilford Brimley, and a passel of his retired pals. It’s a romp.

But it’s a romp about old people. Like Wilford Brimley. Who was my age, starring in a movie about finding yourself at the end of your life, bored and tired and resentful and unsure that any of it meant anything at all.

We suffer and celebrate all kinds of “lines” in our lives; events and measurements that divide everything into before and after. Before we had kids. After they moved out. Before my beloved died. After I learned how to live again. Before I got my degree. After I got my dream job.

The Brimley Line is a jokey way to approach a serious question I’ve been asking myself: What does it feel like to be the age I am? How much time might I have left to do the work I love, spend holidays with my parents, take car trips with my (just about grown) kids? What does it look like to be present, exactly where I am, right now?

I love Richard Rohr’s book Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life, where he says there’s a very personal “before” and “after” for all of us. There’s a thing you’re meant to do in this world God still loves, he says. And when you find it, or it finds you, you realize that everything up to now has been preparatory for this good work. Everything. Even the hard, horrible stuff.

In my memoir of Galileo Church’s first five years, I attest that I’ve found the work I was born for. It’s amazing; I still can’t quite believe I’m this lucky. The work has required, or invited, a reevaluation of everything that came before Galileo: the fundagelical church I grew up in, even as it stunted my spiritual growth… the crippling depression I suffered in college… the embarrassingly bad early relationships… the near meltdown of my marriage, a couple times… the terrifying miscarriages… the kids who are more Holland than Italy, when all I knew was Italian… the frustration of ministry in an institution that is always dying and always denying its death. And more I’m not telling you. Hard, horrible stuff.

And I’m not saying that finding the work I was born for makes all the hard, horrible stuff okay. I can still wish some of that had been different. But as someone who is decidedly on the other side of Rohr’s before/after line, I can attest: it has all been useful.

I keep bumping into this reality about the God who numbers my days: God is frugal AF. God will use whatever we’ve got. God doesn’t throw any of our experiences away, doesn’t wish any of our days away. God just looks at the steaming pile of crap our lives have sometimes become and says, not cheerfully but with compassion for what that crap has cost us, and says, “Okay. We can work with that.”

And here/now, on the other side of the Brimley Line, I’m learning to work with that, too.